Understanding Holdover + Holdunder in Firearms Shooting

If you are in the firearms world, the goal is to impact the target where you are aiming, but is that always the case? Not necessarily. There are many factors that go into whether we need to apply holdover or holdunder to our aiming process. What exactly is holdover and holdunder and how does it apply to my firearm? Holdover and holdunder are terms used to accommodate conditions where the point of aim is purposely adjusted higher than the point of impact (holdover) or adjusted lower than the point of impact (holdunder).

Height over bore

The center bore or interior of the barrel is naturally going to be lower than the sighting mechanism on the firearm because almost all sights sit above the bore, even if the sights are mounted directly to the barrel. This is described as height over bore. The higher the sights are on a firearm, the more the sights will have to move elevation-wise to compensate for the height over bore.

All firearms, regardless of aiming systems, have some measure of height over bore, whether it’s a pistol or a rifle. Firearm manufacturers take this into account when they install the factory sights on a firearm and generally tell the purchaser in the user manual what distance the factory sights are adjusted to, usually represented in a specific diameter group size at a specific distance (Example: holds a 2 inch grouping at 25 yards). The most common need for holdover or holdunder is due to the height of the sights, be it factory iron sights, optical sights (what many call red dots) or magnified scopes.

Distance and Ballistics

There are two key factors that add to the need for holdover and holdunder, namely distance and bullet ballistics. Bullets do not travel in a straight line from the bore to the target. They generally travel in a parabola or similar to the shape of a long rainbow. When shot from a barrel, a bullet starts at bore level, but then gradually gains height, and then over distance will fall due to gravitational pull until it impacts something above the ground or the ground itself. The distance from the target, caliber, grain and velocity of the bullet also impacts how much of a parabola the bullet will travel in. This is where holdover and holdunder can become vastly different whether you are shooting a pistol versus a rifle, but with both types of firearms you first should know what the “zero” of the sights are or where “point of impact” matches “point of aim”.

Rifle Holdover/Holdunder

Most commonly the terms holdover and holdunder are used in long range rifle shooting or hunting. Your rifle with a scope mounted is zeroed to a specific distance for specific ammo.

Some scopes will have hash or dot marks on the scope reticle to apply a specific holdover or holdunder amount of the point of aim based on the distance from the shooter to the target. The scope reticle allows different aiming points based on the distance instead of the shooter estimating where to place the sights to account for holdover or holdunder.

Some rifle scopes have MOA (minute of angle) or MILS/MRAD (milliradian) turret adjustments where you can rotate the turret by “clicks” to adjust the aim point of the scope itself based on distance and bullet ballistics. So based on the distance, the shooter can apply so many clicks up or down to account for holdover or holdunder and then when sighting through the scope, place the crosshairs on the point of impact.

Some rifle scopes have MOA (minute of angle) or MILS/MRAD (milliradian) turret adjustments where you can rotate the turret by “clicks” to adjust the aim point of the scope itself based on distance and bullet ballistics. So based on the distance, the shooter can apply so many clicks up or down to account for holdover or holdunder and then when sighting through the scope, place the crosshairs on the point of impact.

Many rifle shooters will keep track of information to help know what scope adjustments are needed. This is called Data On Previous Engagement (or commonly known as DOPE). It’s where a shooter will track all key information that goes into what scope adjustments may need to be done with the current conditions, based on what they have experienced or experimented with in the past. Want to learn more about DOPE and what it is? Check out this video.

When looking for accuracy as a long range shooter or as a hunter, it’s important that you learn and understand holdover/holdunder for your rifle and scope combination. Here’s some great drills to work on accuracy with a rifle. There’s always a human element that also plays into accuracy beyond sighting the firearm correctly. The Mantis X10 Elite Shooting Performance System attached to your rifle will help identify any input that you are giving to the rifle while you are pressing the trigger so that you can work on correcting and removing any movement during the trigger press.

Pistol Offset

Wait? Do pistol distances warrant using holdover and holdunder? Yes, even factory iron sights are generally manufactured and advertised as sighted to provide a grouping size to a specific distance. There is not a set specification across manufacturers to a zeroed distance. Consider dusting off the owners manual of your pistol if you are unsure of what the distance and grouping size is if you are running factory iron sights on your pistol.

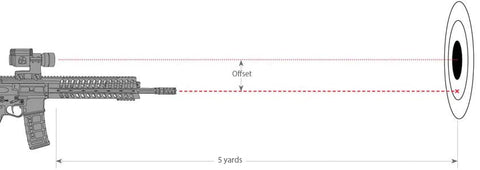

With the introduction of pistol mounted optics, holdover and holdunder are typically called offset or dot offset. Offset is knowing where to place the optic reticle based on the distance the firearm is zeroed to and the distance the target is from the shooter’s position. When an optic is first installed on a firearm, there needs to be a zeroing process by the shooter. Deciding what distance to zero at is a personal choice based on the intended use of the pistol.

A person using a pistol mounted optic for self-defense will typically choose a 10 yard or 25 yard zero. With these distances, shooting at an 8 inch circle (considered size of center mass) the deviation of the point of impact to the point of aim is negligible. Where a person may need to consider using an offset defensively is if they need to take a much longer shot, or if they must engage a smaller target.

The images below show a pistol mounted optic zeroed to 10 yards what the offset would be at 3 yards and 20 yards.

Many pistol/rifle optics do not have the hash marks like a rifle scope to adjust the aim, it’s just adjusting the dot approximately on the target to account for the holdover or holdunder. Some pistol/rifle optics have different reticles in which you can use to help with holdover and holdunder. For example, the Holosun 507 series has a circle (with or without a dot) that has some hash marks that you could use as an aiming point depending on distance for holdover and holdunder.

Practicing with holdover and holdunder

Mantis Laser Academy provides targets in which you can dry fire practice using your pistol or rifle offset. The NRA B-8 target is 8 inches in diameter and the DCS 50 target is great to use together when practicing offset or holdover/holdunder. If you have a 10 yard zero on your pistol, but your target is very small, as in the one inch squares on the DCS 50 target, you may need to apply some holdover, where your point of aim with your optic could be approximately ½ to 1 inch higher than where you want the point of impact to be if you were 3 yards from that target. At the same 3 yard distance you can then take shots without offset on the NRA B-8 target and see that your shots should still land within the black scoring zone without applying any holdover or offset.

Mantis Laser Academy provides targets in which you can dry fire practice using your pistol or rifle offset. The NRA B-8 target is 8 inches in diameter and the DCS 50 target is great to use together when practicing offset or holdover/holdunder. If you have a 10 yard zero on your pistol, but your target is very small, as in the one inch squares on the DCS 50 target, you may need to apply some holdover, where your point of aim with your optic could be approximately ½ to 1 inch higher than where you want the point of impact to be if you were 3 yards from that target. At the same 3 yard distance you can then take shots without offset on the NRA B-8 target and see that your shots should still land within the black scoring zone without applying any holdover or offset.

How can you practice your offset at larger distances that you may not have available in your home? This is where using the 5x7 portable Mantis Laser Academy targets can help simulate distances by reducing the target size. You may find that you need to use holdover or holdunder depending on your zeroed distance, height over bore and distance from the target. The only elements that cannot be accounted for are the ballistic properties of the bullet (weight and velocity). Those factors can only be tested in live fire to calculate the offset.

Regardless of what type of firearm or sighting system you use, there will always be some measure of holdover or holdunder based on the conditions we spoke of above. How do you figure out your holdover or holdunder for your firearm and sighting mechanism? Head out to the range and use the same aiming point and target at multiple distances (3, 5, 7, 10, 15, 20 and 25 yards, if possible) to understand what distance your firearm is zeroed to and how much holdover or holdunder you need to apply to each target based on the distance the target is set at to get the point of impact you desire.

Cara Conry

Author